Orientation

Identification. The terms "Iran" as the designation for the civilization, and "Iranian" as the name for the inhabitants occupying the large plateau located between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf have been in continual use for more than twenty-five hundred years. They are related to the term "Aryan" and it is supposed that the plateau was occupied in prehistoric times by Indo-European peoples from Central Asia. Through many invasions and changes of empire, this essential designation has remained a strong identifying marker for all populations living in this region and the many neighboring territories that fell under its influence due to conquest and expansion.

Ancient Greek geographers designated the territory as "Persia" after the territory of Fars where the ancient Achamenian Empire had its seat. Today as a result of migration and conquest, people of Indo-European, Turkic, Arab, and Caucasian origin have some claim to Iranian cultural identity. Many of these peoples reside within the territory of modern Iran. Outside of Iran, those identifying with the larger civilization often prefer the appellation "Persian" to indicate their affinity with the culture rather than with the modern political state. This is also true of some members of modern Iranian émigré populations in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere who do not wish to be identified with the current Islamic Republic of Iran, established in 1979.

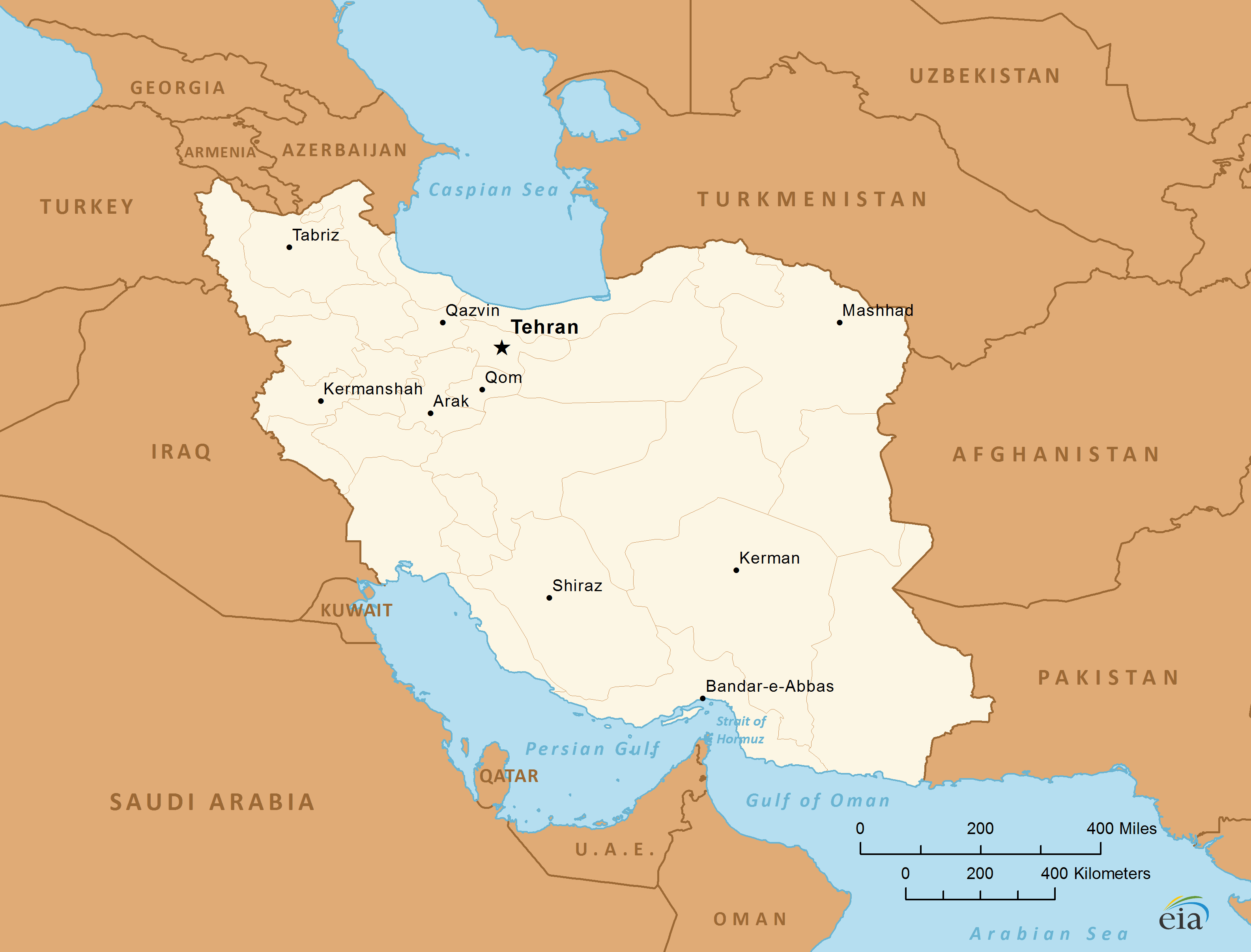

Location and Geography. Iran is located in southwestern Asia, largely on a high plateau situated between the Caspian Sea to the north and the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south. Its area is 636,300 square miles (1,648,000 square kilometers). Its neighbors are, on the north, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkmenistan; on the east, Pakistan and Afghanistan; and on the west Turkey and Iraq. Iran's total boundary is 4,770 miles (7,680 kilometers). Approximately 30 percent of this boundary is seacoast. The capital is Tehran (Teheran).

Iran's central plateau is actually a tectonic plate. It forms a basin surrounded by several tall, heavily eroded mountain ranges, principally the Elburz Mountains in the north and the Zagros range in the west and south. The geology is highly unstable, creating frequent earthquakes. Several important volcanoes, including Mount Damāvand, the nation's highest peak at approximately 19,000 feet, (5,800 meters) also ring the country.

The arid interior plateau contains two remarkable deserts: the Dasht-e-Kavir (Kavīr Desert) and the Dasht-e-Lut (Lūt Desert). These two deserts dominate the eastern part of the country, and form part of an arid landscape extending into Central Asia and Pakistan.

Iran's climate is one of extremes, ranging from subtropical to subpolar, due to the extreme variations in altitude and rainfall throughout the nation. Temperatures range from as high as 130 degrees Fahrenheit (55 degrees Celsius) in the southwest and along the Persian Gulf coast to -40 degrees Fahrenheit (-40 degrees Celsius). Rainfall varies from less than two inches (five centimeters) annually in Baluchistan, near the Pakistani border, to more than eighty inches (two hundred centimeters) in the subtropical Caspian region where temperatures rarely fall below freezing.

Demography

Iran's population is about 80 million. The population is balanced (51 percent male, 49 percent female), extremely young, and urban. More than three-quarters of Iran's habitants are under thirty years of age, and an equal percentage live in urban areas. This marks a radical shift from the mid-twentieth century when only 25 percent lived in cities.

Iran is a multiethnic, multicultural society as a result of millennia of migration and conquest. It is perhaps easiest to speak of the various ethnic groups in the country in terms of their first language. Approximately half of the population speaks Persian and affiliated dialects as their primary language. The rest of the population speaks languages drawn from Indo-European, Ural-Altaic (Turkic), or Semitic language families.

The principal non-Persian Indo-European speakers include Kurds, Lurs, Baluchis, and Armenians, making up approximately 15 percent of the population. Turkic speakers constitute approximately 20 to 25 percent of the population. The largest group of Turkic speakers lives in the northwest provinces of East and West Azerbaijan. Other Turkic groups include the Qashqa'i tribe in the south and southwest part of the central plateau, and the Turkmen in the northeast. Semitic speakers, constituting approximately 10 percent of the population, include a large Arabic-speaking population in the extreme southwest province of Khuzestan, and along the Persian Gulf Coast, and a small community of Assyrians in the northwest, who speak Syriac. The remains of a miniscule community of Dravidian speakers lives in the extreme eastern province of Sistan along the border with Afghanistan.

It is important to note that, with some minor exceptions, all ethnic groups living in Iran, whatever their background or primary language, identify strongly with the major features of Iranian culture and civilization. This also applies to many non-Iranians living in Afghanistan, Central Asia, northern India, and parts of Iraq and the Persian Gulf region.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation.

The Iranian nation is one of the oldest continuous civilizations in the world. Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic populations occupied caves in the Zagros and Elburz mountains. The earliest civilizations in the region descended from the Zagros foothills, where they developed agriculture and animal husbandry, and established the first urban cultures in the Tigris-Euphrates basin in present day Iraq. The earliest urban peoples in what is today Iranian territory were the Elamites in the extreme southwest region of Khuzestan. The arrival of the Aryan peoples—Medes and Persians— on the Iranian plateau in the first millennium B.C.E. marked the beginning of the Iranian civilization, rising to the heights of the great Achaemenid Empire consolidated by Cyrus the Great in 550 B.C.E. Under the rulers Darius the Great and Xerxes, the Achaemenid rulers extended their empire from northern India to Egypt.

Down to the present, one pattern has repeated again and again in Iranian civilization: the conquerors of Iranian territory are eventually themselves

conquered by Iranian culture. In a word, they become Persianized.

The first of these conquerors was Alexander the Great, who swept through the region and conquered the Achaemenid Empire in 330 B.C.E. Alexander died shortly thereafter leaving his generals and their descendants to establish their own subempires. The process of subdivision and conquest culminated in the establishment of the entirely Persian Sassanid Empire at the beginning of the third century C.E. The Sassanians consolidated all territories east to China and India, and engaged successfully with the Byzantine Empire.

The second great conquerors were the Arab Muslims, arising from Saudi Arabia in 640 C.E. They gradually melded with the Iranian peoples, and in 750, a revolution emanating from Iranian territory assured the Persianization of the Islamic world through the establishment of the great Abbassid Empire at Baghdad. The next conquerors were successive waves of Turkish peoples starting in the eleventh century. They established courts in the northeastern region of Khorassan, founding several great cities. They became patrons of Persian literature, art, and architecture.

Successive Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century resulted in a period of relative instability culminating in a strong reaction in the early sixteenth century on the part of a resurgent religious movement—the Safavids. The Safavid rulers started as a religious movement of adherents of Twelver Shi'ism. They established this form of Shi'ism as the Iranian state religion. Their empire, which ranged from the Caucasus to northern India, raised Iranian civilization to its greatest height. The Safavid capital, Isfahan, was by all accounts one of the most civilized places on earth, far in advance of most of Europe.

Subsequent conquests by the Afghans and the Qājār Turks had the same result. The conquerors came and became Persianized. During the Qājār period from 1899 to 1925, Iran came into contact with European civilization in a serious way for the first time. The industrial revolution in the West seriously damaged Iran's economy, and the lack of a modern army with the latest in weaponry and military transport resulted in serious losses of territory and influence to Great Britain and Russia. Iranian rulers responded by selling "concessions" for agricultural and economic institutions to their European rivals to raise the funds needed for modernization. Much of the money went directly into the pockets of the Qājaār rulers, cementing a public image of collaboration between the throne and foreign interests that characterized much of twentieth century Iranian political life. A series of public protests against the throne took place at regular intervals from the 1890s to the 1970s. These protests regularly involved religious leaders, and continued throughout the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979). These protests culminated in the Islamic Revolution of 1978–1979, hereafter referred to as "the Revolution."

National Identity.

The establishment of the theocratic Islamic Republic of Iran under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini marked a return to religious domination of Iranian culture. Khomeini's symbols were all appropriately appealing to Iranian sensibilities as he called on the people to become martyrs to Islam like Hasan, and restore the religious rule of Hasan's father, Ali, the last leader of both Sunni and Shi'a Muslims.

Ethnic Relations. Iran has been somewhat blessed by an absence of specific ethnic conflict. This is noteworthy, given the large number of ethnic groups living within its borders, both today and in the past. It is safe to conclude that the general Iranian population neither persecutes ethnic minorities, nor openly discriminates against them.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Until recently Iran was primarily a rural culture. Even today with rampant urbanization, Iranians value nature and make every attempt to spend time in the open air. Because Iran is largely a desert, however, the ideal open space is a culturally constructed space—a garden. At the same time Iranians will try to bring the outdoors inside whenever possible. The wonderfully intricate carpets that every family strives to own are miniature gardens replete with flower and animal designs. Fresh fruit and flowers are a part of every entertainment, and nature and gardens are central themes in literature and poetry.

This underscores a fascinating central motif in Iranian architecture—the juxtaposition of "inside" and "outside." These two concepts are more than architectural themes. They are deeply central to Iranian life, pervading spiritual life and social conduct. The inside, or andaruni , is the most private, intimate area of any architectural space. It is the place where family members are most relaxed and able to behave in the most unguarded manner. The outside, or biruni , is by contrast a public space where social niceties must be observed. Every family creates both kinds of spaces, even if living in a single room. Until the nineteenth century, Iranians did not use chairs. They normally sat cross-legged on the floor, preferably on a carpet with bolsters or pillows. In the twentieth century, furniture became the hallmark of the biruni , and now every family of any standing has a room stuffed with uncomfortable furniture for receiving important visitors. When the guests leave, family members give a sigh of relief and go to the andaruni where they can relax on the plush carpet.

An Iranian home is one where any room, with the exception of those used for cooking and bodily functions, can be used for any social purpose— eating, sleeping, entertainment, business, or whatever else one can conceive. One spreads a dinner cloth, and it is a dining room. After dinner, the cloth is removed, cotton mattresses are spread, and the room becomes a bedchamber. Contrast this to an American home where each room has specific functions, or is designated the specific territory of a given family member. As a result, Iranian families can live and entertain many guests in much less space than in the West. This is a social necessity, since the members of one's extended family, and even their friends and acquaintances, have an ironclad claim on virtually unlimited hospitality. One must be prepared to entertain many overnight guests at a moment's notice.

In addition to intimacy, the notion of the andaruni pertains to modesty for women. This is a consideration in all public arrangement of space, especially since the advent of the Islamic Republic. Some zealots will not allow men to sit on a spot that is still warm from a woman's presence. By contrast, public space occupied by persons of the same sex can be very close and intimate with no hint of eroticism or immodesty.

The historical Iranian city is constructed around the commercial center—the bazaar. Architect Nader Ardalan has likened the city to the human body. The bazaar is the spine of the city. Emanating from it are all the institutions needed by the urban population. At the top of the bazaar sits the "head" of this body—the great congregational mosque where all citizens gather on Friday for common prayers and perhaps a sermon. The bazaar is divided into sections inhabited by the various trade guilds. Thus all the carpenters are in one section, the goldsmiths in another, and the shoemakers in yet another.

The bazaar is punctuated with the "outside brought inside" in the form of pools and running water, and even perhaps a religious school with a small garden. The urban space surrounding the bazaar is likewise punctuated by the "inside brought outside" in the form of enclosed public gardens for private discourse in public. Houses in residential neighborhoods are built with abutting walls, each home having its bit of the outside in the form of an open courtyard with a pool, and a tree and a few flowers or a kitchen garden.

In the twentieth century, however, the needs of modern motor transportation and increased urban population density have destroyed much of the texture of the traditional city. Wide avenues have been cut through the traditional quarters in almost every city, disrupting the integrity of the old neighborhoods. Faceless apartment buildings have sprung up depriving residents of their gardens, save for a pot or two of flowers on a small balcony.

Public architecture has always been the essence of biruni in Iran. Grandiose in style, it almost demands formal social behavior. This has been true since Achaemenid times, as a visit to the ruins of their capital, Persepolis, will attest. The grandiose public mosques, shrines, and squares of Isfahan, Mashhad, Shīrāz, and Qom are overwhelming in their beauty and architectural excellence. Unfortunately, the great public buildings of Tehran built in the twentieth century have the bad fortune to have been built to emulate the most stark Western architectural styles.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. In Iran women control marriages for their children, and much intrigue in domestic life revolves around marital matters. A mother is typically on the lookout for good marriage prospects at all times. Even if a mother is diffident about marriage brokering, she is obliged to "clear the path" for a marriage proposal. She does this by letting her counterpart in the other family know that a proposal is forthcoming, or would be welcome. She then must confer with her husband, who makes the formal proposal in a social meeting between the two families. This kind of background work is essential, because once the children are married, the two families virtually merge, and have extensive rights and obligations vis-á-vis each other that are close to a sacred duty. It is therefore extremely important that the families be certain that they are compatible before the marriage takes place.

Marriage within the family is a common strategy, and a young man of marriageable age has an absolute right of first refusal for his father's brother's daughter—his patrilateral parallel cousin. The advantages for the families in this kind of marriage are great. They already know each other and are tied into the same social networks. Moreover, such a marriage serves to consolidate wealth from the grandparents' generation for the family. Matrilateral cross-cousin marriages are also common, and exceed parallel-cousin marriages in urban areas, due perhaps to the wife's stronger influence in family affairs in cities.

Although inbreeding would seem to be a potential problem, the historical preference for marriage within the family continues, waning somewhat in urban settings where other considerations such as profession and education play a role in the choice of a spouse. In 1968, 25 percent of urban marriages, 31 percent of rural marriages, and 51 percent of tribal marriages were reported as endogamous. These percentages appear to have increased somewhat following the Revolution.

In Iran today a love match with someone outside of the family is clearly not at all impossible, but even in such cases, except in the most westernized families, the family visitation and negotiation must be observed. Traditional marriages involve a formal contract drawn up by a cleric. In the contract a series of payments are specified. The bride brings a dowry to the marriage usually consisting of household goods and her own clothing. A specified amount is written into the contract as payment for the woman in the event of divorce. The wife after marriage belongs to her husband's household .

The wedding celebration is held after the signing of the contract. It is really a prelude to the consummation of the marriage, which takes place typically at the end of the evening, or, in rural areas, at the end of several days' celebration. In many areas of Iran it is still important that the bride be virginal, and the bedsheets are carefully inspected to ensure this. The new couple may live with their relatives for a time until they can set up their own household. This is more common in rural than in urban areas.

Iran is an Islamic nation, and polygyny is allowed. It is not widely practiced, however, because Iranian officials in this century have followed the Islamic prescription that a man taking two wives must treat them with absolute equality. Women in polygynous marriages hold their husbands to this and will seek legal relief if they feel they are disadvantaged. Statistics are difficult to ascertain, but one recent study claims that only 1 percent of all marriages are polygynous.

Divorce is less common in Iran than in the West. Families prefer to stay together even under difficult circumstances, since it is extremely difficult to disentangle the close network of interrelationships between the two extended families of the marriage pair. One recent study claims that the divorce rate is 10 percent in Iran.

Children of a marriage belong to the father. After a divorce, men assume custody of boys over three years and girls over seven. Women have been known to renounce their divorce payment in exchange for custody of their children. There is no impediment to remarriage with another partner for either men or women.

Domestic Unit. In traditional Iranian rural society the "dinner cloth" often defines the minimal family. Many branches of an extended family may live in rooms in the same compound.Sons and their wives and children are often working for their parents in anticipation of a birthright in the form of land or animals. When they receive this, they will leave and form their own separate household. In the meantime they live in their parents' compound, but have separate sleeping arrangements. Even after they leave their parents' home, members of extended families have widespread rights to hospitality in the homes of even their most distant relations. Indeed, family members generally carry out most of their socializing with each other.

Inheritance.

Inheritance generally follows rules prescribed by Islamic law. Male children inherit full shares of their father's estate, wives and daughters half-shares. An individual may make a religious bequest of specific goods or property that are then administered by the ministry of waqfs.

Kin Groups. The patriarch is the oldest male of the family. He demands respect from other family members and often has a strong role in the future of young relatives. In particular it is common for members of an extended family to spread themselves out in terms of professions and influence. Some will go into government, others into the military, perhaps others join the clergy. Families will attempt to marry their children into powerful families as much for their own sake as for the son or daughter. The general aim for the family is to extend its influence into as many spheres as possible. As younger members mature, older members of the family are expected to help them with jobs, introductions, and financial support. This is not considered corrupt or nepotistic, but is seen rather as one of the benefits of family membership.

Medicine and Health Care

Health care in Iran is generally very good. Life expectancy is relatively high (70 years) and the nation does not have any severe endemic infectious diseases. The principal cause of death is heart and circulatory disease. Many physicians emigrated at the time of the Islamic Revolution.

Health care programs in recent years have been highly successful. Malaria has been virtually eliminated, cholera and other waterborne diseases are generally under control, and family planing programs have resulted in dramatic decreases in fertility rates. The infant mortality rate remains somewhat elevated (twenty-nine per thousand) but it has declined significantly over the past twenty years. AIDS figures are suppressed. A high percent of medicine produce in the country (less than 8% import )and even in the last years started to export to many country around and even some European country.

A folk belief prevalent in Iran revolves around dietary practice. This philosophy tries to maintain balance between the four humors of the body— blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—through judicious combinations of foods. Although more sophisticated Iranians use the full range of four humors in their dietary calculations, most adhere to a two-category system: hot and cold. For example, visitors quickly learn that their friends will not allow the simultaneous consumption of watermelon and yogurt (both cold foods) Or mix of melon an honey (both hot foods), for fear that this combination will cause immediate death.

Etiquette

The social lubricant of Iranian life is a system known as ta'arof , literally "meeting together." This is a ritualized system of linguistic and behavioral interactional strategies allowing individuals to interrelate in a harmonious fashion. The system marks the differences between andaruni and biruni situations, and also marks differences in relative social status. In general, higher status persons are older and have important jobs, or command respect because of their learning, artistic accomplishments, or erudition.

Linguistically, ta'arof involves a series of lexical substitutions for pronouns and verbs whereby persons of lower status address persons of higher status with elevated forms. By contrast, they refer to themselves with humble forms. Both partners in an interaction may simultaneously use other-raising and self-lowering forms toward each other. Ritual greetings and leave-takings such as ghorban-e shoma (literally, "your sacrifice") underscore this sensibility.

In social situations, this linguistic gesture is replicated in behavioral routines. It is good form to offer a portion of what one is about to eat to anyone nearby, even if they show no interest. One sees this behavior even in very small children. It is polite to refuse such an offer, but the one making the offer will be sensitive to the slightest hint of interest and will continue to press the offer if it is indicated.

Guests bring honor to a household, and are eagerly sought. When invited as a guest a small present is appreciated, but often received with a show of embarrassment. It will usually not be unwrapped in front of the giver. It is always expected that a person returning from a trip will bring presents for family and friends.

An honored guest is always placed at the head of a room or a table. The highest status person also goes first when food is served. It is proper form to refuse these honors, and press them on another.

One must be very careful about praising any possession of another. The owner will likely offer it immediately as a present. Greater danger still lies in praising a child. Such praise bespeaks envy, which is the essence of the "evil eye." The parent will be alarmed, fearing for the child's life. The correct formula for praising anything is ma sha' Allah , literally, "What God wills."

Iranians can be quite physically intimate with same-sex friends, even in public. Physical contact is expected and is not erotic. In restaurants and on buses and other public conveyances people are seated much closer than in the West. On the other hand, even the slightest physical contact with non-family members of the opposite sex, unless they are very young children, is taboo.

A downward gaze in Iran is a sign of respect. Foreigners addressing Iranians often think them disinterested or rude when they answer a question without looking at the questioner. This is a cross-cultural mistake. For men, downcast eyes are a defense measure, since staring at a woman is usually taken as a sign of interest, and can cause difficulties. On the other hand, staring directly into the eyes of a friend is a sign of affection and intimacy.

In Iran the lower status person issues the first greeting. In the reverse logic of ta'arof this means that a person who wants to be polite will make a point of this, using the universal Islamic salaam or the extended salaam aleikum. The universal phrase for leave-taking is khoda hafez —"God protect."